Have you heard of flow? If not, you’ve probably heard of the zone. Being in the zone and experiencing flow are two similar ways to describe optimal experiences while completing a task. It’s just that being “in the zone” is used more colloquially, and flow is the official term used in sports psychology. It turns out that athletes perform better when experiencing flow and that mindfulness meditation for athletes can help them experience flow. This is really good news for high-performance coaches and athletes.

Since 1992, numerous studies have been conducted about flow and its relationship to optimal experience and performance in sport. Researchers have even discovered ways to induce flow or train athletes to experience flow more easily by introducing mindfulness meditation for athletes into their training routines.

At Ertheo, we investigated this new field of sports psychology to learn more about new findings in mindfulness meditation research and its relationship to flow, sports anxiety, and enhanced sports performance. Then, we reached out to mindfulness meditation experts all around the world to help us create a list of mindfulness meditation exercises to help reduce sports anxiety and improve sports performance.

Contents

Download the free eBook for exclusive access to 5 meditation exercises specially designed for athletes. No email required.

Experiencing flow

Let’s talk about the zone first

The zone is a figurative mental space where extreme focus and attention give us a sort of tunnel-vision that enhances our performance or productivity and chances our perception of time. When we’re in the zone, we’re so focused on whatever we’re doing that we’re almost in our own worlds, removed from the real world around us.

Many of us get in the zone in different ways during different activities. Some of us get in the zone while creating, so completely focused on our art that we forget to eat dinner. Others get in the zone while studying in the library or writing a paper. All of a sudden, we look outside the library window and it’s dark because time flew by. Often times, we get in the zone at work. Those tend to be our most productive days.

Athletes often describe what it’s like to get in the zone during their best performances. Connor McGregor, former UFC champion, describes his experience in the ring: “When I’m in there, I’m just in my zone. What people think about what they look at me, that’s their business.”

Mark Calcavecchia, 13 time PGA tour winner, described his experience on the golf course: “When I’m in the zone, I don’t think about the shot, or the wind, or the distance, or the gallery, or anything. I just pull a club and swing.”

“When I’m in the zone, I don’t think about the shot, or the wind, or the distance, or the gallery, or anything. I just pull a club and swing.”

∼ Calcavecchia, 13 time PGA tour winner

The zone is a joyful place. When we get in the zone, we’re usually too focused to feel joyful. We might not consciously feel joy at work or while completing an important project. But afterward, we usually think about our performance and accomplishment with contentment. At the same time, we’re often exhausted and probably wouldn’t choose to complete an intense soccer training program with no end goal. That being said, recent research on the zone has found that after spending some time in the zone experiencing flow, we feel like our life has meaning and purpose.

Why do we call it flow?

Shortly after witnessing the destruction of WWII in Europe, American-Hungarian psychologist Mihály Csíkzentmihályi became highly interested in what makes people happy in their everyday lives and what gives their lives meaning. He conducted numerous interviews with creative people in pursuit of an answer and found that most people experience happiness when they are so involved in their work, that they lose touch with reality. In other words, people are happiest when they’re in the zone.

Want the full story? Watch Csíkzentmihályi explain for himself!

https://embed.ted.com/talks/lang/en/mihaly_csikszentmihalyi_on_flow

However, while athletes often use “the zone” to describe optimal experiences within the sport, Csíkzentmihály found that creative people (artists, musicians, writers, and athletes alike) describe their optimal experience as a kind of flowing. In 1972, Csíkzentmihályi published a book called Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience where he talked about the state of being in the zone. He called it flow, and described all of the many benefits that experiencing flow can have on human experience.

What does flow feel like?

Csíkzentmihályi described experiencing flow as “being completely involved in an activity for its own sake. The ego falls away. Time flies. Every action, movement, and thought follows inevitably from the previous one, like playing jazz. Your whole being is involved and you’re using your skill to the utmost.” [1]

Csíkzentmihályi’s description is a good description, but it’s quite poetic. Here’s a little outline:

- You lose awareness of time – Athletes who experience flow often describe how the clock seemed to slow down or stop.

- Self-consciousness fades away. – Athletes experiencing flow often describe their indifference to the crowd and how the crowd responds to their actions.

- You’re focused only on the present moment. – Athletes experiencing flow often describe an intense focus on the task. “It was just me and the basket,” they might say.

- Your work, in the moment, seems fluid and effortless. – Athletes experiencing flow describe their experiences as easy and usually free of thought. Their body just leads them to victory.

So, not only are people happiest when they’re in the zone or experiencing flow, but they’re also most productive. Sounds good, right? Wouldn’t it be great if there was a special formula to help athletes experience flow? Good news, there is.

Discussion

We’ve learned the difference between being in the zone and experiencing flow. Athletes often describe what it feels like to be in the zone, and we can think of experiencing flow and being in the zone as the same thing. Flow is just the term used in sport psychology, and therefore, flow is a more tested phenomenon than the zone.

We’ve also learned a little about the history of flow. Why did researchers begin testing flow? Flow was initially a part of happiness research. Being in flow makes us happy.

Finally, we learned a little about what flow is and what it feels like, the signs and symptoms of experiencing flow if you will.

In the next section, we’ll explore flow in depth. We’ll talk about the 9 dimensions of flow and how they can be applied to sport. Then, we talk about how experiencing flow can actually improve sports performance. Finally, we’ll discuss some limiting factors of flow.

What to skip ahead? Click one of the links below.

Mindfulness meditation and flow: How can mindfulness meditation for athletes help them experience flow and perform better?

5 Meditation exercises for athletes: Meditation exercises designed by experts especially for athletes

Dimensions of flow

How do we get into flow?

Some people experience the dimensions of flow more easily than others. Csíkzentmihályi says that people with autotelic personalities are more likely to experience the dimensions flow. “Autotelism is the belief that satisfying work is justification in and of itself. The autotelic personality traits include curiosity, persistence, low self-centeredness, and a desire of performing activities for intrinsic reasons only.” [1]

Likewise, researchers have tested the relationship between personality traits and flow experience in amateur vocalist students. They found that flow state is easier to experience for extraverted students. They also found that for more neurotic students, the dimensions of flow were more difficult to experience. [2] Fortunately, flow isn’t entirely dependent on personality traits. Many external factors contribute to the likelihood of experiencing flow in any given activity.

Autotelic personalities are more likely to experience flow.

What are the 9 dimensions of flow? How do they relate to sport?

Csíkzentmihályi put together a sort of formula for achieving flow. He outlined nine elements of flow that both enable and describe flow experience. They are:

- Challenge-skill balance

- Action-awareness merging

- Clear goals

- Unambiguous feedback

- Total concentration on the task at hand

- Sense of control

- Loss of self-consciousness

- Transformation of time

- Autotelic experience

When a person experiences all nine elements at the same time, they are experiencing an optimal flow experience. However, people can experience some dimensions of flow independently of others. In which case, they’d be experiencing a partial flow state.

It turns out that athletes can experience all nine dimensions of flow when practicing their sport, and when they do, they rate their performance better. [3] We’ll talk about how flow can improve sports performance in the next section. For now, let’s explore the nine dimensions of flow according to Csíkzentmihályi and how they relate to sport.

1. Challenge-skill balance

Flow state requires a balance between our perception of challenge level and skill level. This means we should feel confident that we have the skills to complete the task while at the same time recognizing that completing the task would require our full concentration and attention on the challenge at hand and on the present moment.

In sports, as athletes improve their skills, the challenge level increases. They either move up a level and compete against better components or give themselves new challenges to overcome. Sports provide athletes with the opportunity to continue challenging themselves and continue improving which is also what makes them enjoyable.

2. Action-awareness merging

Flow state often produces a feeling of unity between action and awareness. That is, during flow, we might describe feeling at one with whatever task we’re doing. Our mind is completely present in the activity, undistracted by other life events or challenges that might cause us pain or anxiety in our daily lives. During flow, all consciousness of the world outside of the activity simple fades away, and we feel at one with the task.

In many aspects of sports, athletes act almost automatically, using their muscle memory to perform well-learned skills. That way, they can focus on the more complex aspects of their sport. For example, advanced tennis players might not need to consciously think about how to hit the ball. They might, however, think about where to hit the ball to put them in an advantageous position to win the point. To advanced athletes, simpler aspects of their sport come naturally. Tennis players feel at one with their rackets, so to speak. This frees up their ability to think more complexly and strategically and experience flow.

3. Clear goals

Flow state also requires clear goals. To enter flow, we must be able to describe exactly what we’re supposed to do before attempting to complete the task. That way, during the activity, we can focus all of their attention on achieving the goal.

Clear goals are woven into the rules and framework of sports. Athletes must score, earn a certain amount of points, be the fastest, etc. Even outside of the context of winning, clear goals are a key element in sports. In soccer, the end goal might be to score more goals that the opposing team. During the match, players know to maintain possession, make clean passes, win the ball back on defense, etc. All of which are clear goals that soccer players understand before the match which, therefore, facilitate flow.

4. Unambiguous feedback

Unambiguous feedback about how we’re performing is another key element of flow. To experience flow, we must receive positive feedback about our performance. Feedback can be received a number of ways. Sometimes the feedback comes from an outside source. Sometimes it comes simply from meeting our clear goals.

For athletes, feedback comes from a range of factors, often at the same time. Athletes receive feedback from their own kinesthetic awareness of how their bodies are moving through space. When a diver perfects a dive or a gymnast perfects a flip, they don’t need the judges’ scores to feel that they’ve done a good job. However, most of the time, athletes do receive additional feedback from judges, fans, coaches, or simply meeting their goals. The feedback athletes receive as they perform facilitates flow.

5. Total concentration on the task at hand

Total concentration on the task is one of the clearest indications of experiencing flow and is highly related to a challenge-skill balance. When our skill level is just high enough to accomplish the task, in order to really accomplish it, we need complete focus. In doing so, we forget about all the anxiety and troubles of daily life and enjoy the present moment. If we are able to complete the task while thinking about what we’re cooking for dinner that night, our thoughts are likely to wander from the present moment and take us out of flow.

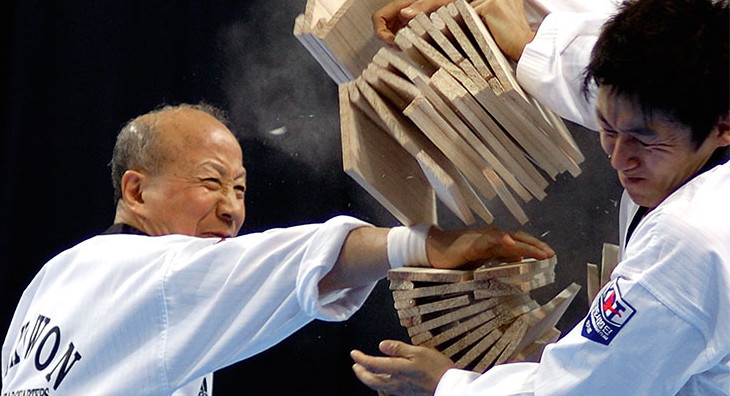

This fifth element is one of the most important for experiencing flow. Most sports have the potential to provide enough challenge to require an athlete’s complete concentration, especially at an advanced level. While some sports require complete physical control and concentration, other sports require more brain power to play strategically. In general, most individual sports without a face to face component, like gymnastics, for example, require more physical control and concentration. Other sports, especially team sports like soccer, hockey, American football, etc., require a lot of brain power to play strategically based on the moves of their own team and opponents. Martial arts are especially flow-inducing sports because they require a balance of concentration on the mind and on the body.

6. Sense of control

The sixth element of flow is a sense of control, which is closely related to a challenge-skill balance. Notice, the key to experiencing the sixth dimension of flow is a sense of control, not complete control. Complete control would imply that we easily have the skills to complete the task. A sense of control, however, implies that while we have just enough skills to complete the task if we focus all our attention on what we’re doing in the present moment. On the other hand, if our skills reside far below the challenge level, we might feel out of control and start to doubt our abilities. This doubt would take us out of the present moment and out of flow.

Sports provide the perfect environment to experience a sense of control without complete control. As soon as athletes start to lean toward experiencing complete control, they tend to push themselves to accept new challenges to advance in the sport. As a diver perfects 1.5 somersaults in the tuck position, they might try for a slightly more difficult dive. When a soccer team starts to win almost all of their games, they move up to a higher division. When a climber starts to feel comfortable on a certain type of cliff, they might look for a slightly steeper or higher cliff. When athletes push themselves to accept new challenges without pushing themselves too far, they maintain a sense of control. This balance establishes flow.

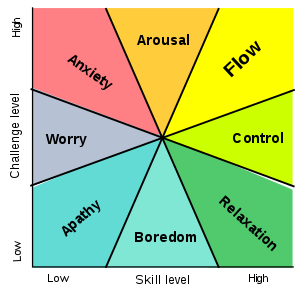

The image below is a visual demonstration of the state of flow in comparison with other states we experience. As you can see, we feel complete control when the challenge level is moderate, but our skills are advanced. Flow is located just above control where our skills are advanced, but the challenge level is also advanced, requiring our complete attention.

7. Loss of self-consciousness

Loss of self-consciousness is another important element of flow. Most of us live our lives consistently evaluating and judging ourselves and worrying about judgment from others. When we’re self-conscious, we’re unfocused, distracted by thought, and out of touch with the present moment. That’s why the loss of self-consciousness is an important aspect of flow – because self-consciousness distracts us from the task at hand. That’s also why the balance of skill and challenge level and complete concentration on the task at hand are so important for flow. When we need full concentration to complete a task, we can’t let self-conscious thoughts distract us, or we’ll fail.

Some athletes are more likely to experience a loss of self-consciousness during their performances than others. Many athletes find it difficult to perform during competitions or in front of crowds because they’re worried about judgment from spectators or coaches. This is called performance anxiety. Performance anxiety is a major problem for many athletes because this self-consciousness is often very difficult to control. It’s hard to break the habit of self-judging, but athletes must break this habit and let go of self-consciousness to experience flow and perform optimally.

8. Transformation of time

The transformation of time refers to our perception of time. Deeper flow experiences have the power to make us experience time as passing faster or slower than it is in reality. When we’re focused so intensely on a task in the present moment, time seems to fade away or have little importance.

This dimension of flow can be quite difficult for athletes to experience because for many sports, wins or losses are determined based on a specific period of time. As a result, players are very conscious of winning time or wasting time. Other sports, like tennis, are played until a certain outcome is reached. The importance of time in a sport can influence an athlete’s ability to experience the transformation of time. Otherwise, whether or not an athlete experiences this dimension of flow highly depends of their personality.

9. Autotelic experience

An autotelic experience is one that is intrinsically rewarding. This means we do the activity because the activity in itself makes us feel good, not because we receive external rewards like money, status, approval, etc., although such outcomes may result. Csikszentmihalyi said that in many cases, flow experiences bring us so much joy that we seek them out and they become autotelic. It’s not until after the flow experience, however, that we experience this joy because during flow, we’re often too focused on the task to fully experience joy.

Most sports were invented for the sake of enjoyment. When we first began kicking balls around and shooting balls in baskets, we didn’t do it for fame or fortune. We probably started doing it because we were bored and thinking of ways to enjoy our newfound free time. After all, many of the world’s most popular sports today were invented in the late 1800s, right after the industrial revolution. With new machines doing all our fieldwork, we had more time to sit around and think of new ways to have fun. Unfortunately, the pressure to perform and win keeps many athletes from enjoying their sport. Others enjoy the pressure and competition and such pressure adds to the enjoyment of the sport. All in all, it’s much easier to experience flow when we play a sport because we love it.

How can flow improve our sports performance?

Since Csíkzentmihályi began researching flow in the 70s, researchers have been interested in the relationship between flow and peak sports performance where flow is an internal state, and peak performance refers to performing optimally.

In 1992, researchers found that athletes who were performing optimally reported experiencing total commitment, clearly defined goals, feedback about how well they were performing, concentration on performing the activity, task-relevant thoughts, sense of control, and feelings of fun, confidence, and enjoyment. Basically, athletes who were performing optimally were experiencing all nine dimensions of flow. [4]

Later, researchers found that “athletes in flow and relaxation states revealed the most optimal states, whereas athletes in apathy states showed the least optimal state. [In addition, they found] positive associations between athletes’ flow experience and their performance measures, indicating that positive emotional states are related to elevated levels of performance.” [5]

All in all, research indicates that flow is an optimal internal state that likely results in improved sports performance. That means if we want to perform at our best potential, we should try to experience flow whenever possible. As mentioned earlier, however, experiencing flow is easier for some people than for others. Let’s talk about the common limitations of flow experience and how to overcome them.

What keeps us from experiencing flow?

Researchers have found that some main limitations of flow for athletes are sports anxiety and general pessimistic thinking. [6]

Athletes who suffer from sports anxiety constantly worry about their performance in general, their ability to perform during competitions, and/or injury or illness that could set them back during or before competitions. Read more about common mental game challenges at sportspsychologytoday.com.

Let’s think back to the seventh dimension of flow, “lack of self-consciousness.” Sports anxiety is directly related to enhanced self-consciousness and, therefore, completely disrupts flow.

Furthermore, anxiety experienced by elite athletes over illness symptoms is linked to the risk of being injured during competition. In one specific study, athletes who were anxious about illness symptoms before competition were five times more likely to suffer an injury. [7]

That being said, sports anxiety not only prohibits athletes from experiencing flow and therefore performing below their potential. Sports anxiety is also physically dangerous for athletes.

Conclusion

In this section, we learned all about flow. We learned about all nine dimensions of flow and how they relate to sport. We also learned that in recent research, experiencing the dimensions of flow has been linked to better sports performance. Finally, we discussed some limits to achieving flow, namely, sports anxiety. Athletes, especially high-performance athletes, experience great anxiety about their sport. Some feel anxious about how they’ll perform in front of a crowd. Others worry about getting injured ruining their chances of becoming great. This anxiety makes it really hard for athletes to experience the dimensions of flow like lacking self-consciousness and merging awareness and action.

Fortunately, mindfulness meditation for athletes can help ease this anxiety and help them stay focused on the present moment, the task at hand. In the next section, you’ll learn all about this practice and how it can help athletes experience all dimensions of flow.

Mindfulness meditation and flow

How can mindfulness meditation reduce sports anxiety and increase our likelihood to experience flow?

Recent research suggests that mindfulness meditation for athletes can help them control negative thoughts and sports anxiety which allows them to focus on their skills in the present moment and perform better. [8]

Additionally, researchers have found that athletes with higher levels of mindfulness are more likely to experience various dimensions of flow including challenge-skill balance, clear goals, concentration, merging of action and awareness, and loss of self‐consciousness [9]. This research suggests that mindfulness may be a catalyst for flow.

Here’s some more proof:

In 2009, researchers found that Mindfulness Sport Performance Enhancement (MSPE) training enhances flow, mindfulness, and aspects of confidence which could lead to improved performance. [10]

In 2015, researchers found that Mindful Performance Enhancement, Awareness and Knowledge (mPEAK) training improves the ability to identify and describe feelings and reactions to bodily sensations which means mPEAK training could help athletes adapt to high stress and develop more resilience. [11]

In 2016, researchers tested the effects of the Mindfulness-integrated Cognitive Behavior Therapy (MiCBT) program on cyclists. Results suggested that mindfulness-based interventions tailored to specific athletic pursuits can be effective in facilitating flow experiences and, therefore, enhancing athlete performance. [12]

The relationship between mindfulness meditation, flow, and peak performance is a relatively new field in sports psychology. Nevertheless, researchers are fairly certain that:

- Flow results from positive self-concept and self-confidence

- Flow is related to optimal performance

- Sports anxiety inhibits the flow experience

- Meditation mindfulness can help control sports anxiety

That being said, mindfulness meditation for athletes might be the key to reducing sports anxiety and unlocking flow so that athletes can perform optimally.

Read more about the proven benefits of mindfulness

What is mindfulness meditation?

Let’s talk about the difference between mindfulness, meditation, and mindfulness meditation. While mindfulness is often described as a state, meditation is often described as an exercise.

According to Giovanni Dienstmann, meditation expert and certified teacher,

“Meditation is a mental exercise of regulating attention. It is practiced either by focusing attention on a single object, internal or external (focused attention meditation) or by paying attention to whatever is predominant in your experience in the present moment, without allowing the attention to get stuck on any particular thing (open monitoring meditation).”

Mindfulness, on the other hand, is often described as a state of awareness. According to the Greater Good Magazine at UC Berkeley,

“Mindfulness means maintaining a moment-by-moment awareness of our thoughts, feelings, bodily sensations, and the surrounding environment, through a gentle, nurturing lens. Mindfulness also involves acceptance, meaning that we pay attention to our thoughts and feelings without judging them—without believing, for instance, that there’s a “right” or “wrong” way to think or feel in a given moment.”

Happify says that meditation exercises can help increase our ability to be mindful. Watch the video below by Happify to learn more about mindfulness and how meditation mindfulness is a superpower.

“Mindfulness is a superpower, and the way to get it is through meditation.”

Let’s recap. Mindfulness is a state of being that requires self-awareness without self-judgment. By practicing this self-awareness, we can learn to simply feel our emotions without getting carried away by them. This means, that we don’t let our thoughts make us any more angry, jealous, nervous, etc. than we already feel, but we don’t judge ourselves for feeling the way we feel either.

There are many different mindfulness meditation exercises we can do to improve our mindfulness in our daily lives. Similarly, athletes can practice specific mindfulness meditation for athletes to improve their mindfulness as they practice their sport. Regardless of which mindfulness meditation exercises you practice, it’s important to follow some basic guidelines to ensure you make the most out of the exercises. Check out these guidelines from mindful.org:

Mindfulness meditation guidelines

There’s no way to quiet your mind. Quieting your mind is not the goal. The goal is to be aware of your mind.

Your mind will wander. When practicing mindfulness meditation, it’s normal for your mind to wander and think about something that happened to you yesterday or your to-do list, for example.

As your mind wanders, simply bring it back to the present moment. This is the great advantage of mindfulness meditation – learning to recognize when your mind has wandered to the past or future so that you can bring it back to the present moment.

Don’t judge yourself for your wandering mind. When you judge yourself, your mind is in the past. Instead of judging or criticizing yourself for letting your mind wander, simply bring your mind back to your breath and your body in the present moment.

Use your breath as an anchor to the present moment. Take deep breaths from your belly as you complete meditation mindfulness exercises. Even during body scans or muscle relaxation exercises, deep breathing is essential to connect your body and mind to the present moment.

Conclusion

In this section, we learned all about mindfulness, meditation, and mindfulness meditation. We learned that while meditation is a practice, mindfulness is a state of mind, and meditation is a great way to develop mindfulness. We also learned that current research supports the idea that mindfulness programs for athletes can actually help athletes perform better by making it easier for them to experience flow.

Download the eBook for 5 meditation exercises specially designed for athletes and coaches. Just click below. No email required.

5 Meditation exercises for athletes

At Ertheo, we’ve collaborated with mindfulness meditation experts around the world who specialize in mindfulness meditation for athletes. Together, we’ve put together a list of mindfulness meditation exercises for coaches and/or athletes to incorporate into their training.

- Diaphragmatic Breathing Exercise with Power Pose

- Mindful Body Scan

- Full-Body Progressive Muscle Relaxation

- Soccer Visualization

- Mindful Walking Meditation

Contributions

A special thanks to all those who contributed to this project. Click the links below to learn more about them.

Pavan Mehat Sustainable Athletics

Mindfulness for Students

Reading suggestions:

Skills to achieve success in soccer – Do you have all 12?

Coaching youth soccer – 5 SECRETS to improve performance

Discover the best international soccer camps and programs

References

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York: Harper & Row.

- Heller, K., Bullerjahn, C., & von Georgi, R. (2015). The Relationship Between Personality Traits, Flow-Experience, and Different Aspects of Practice Behavior of Amateur Vocal Students. Frontiers in psychology, 6, 1901.

- Jackson, Susan & Thomas, Pat & Marsh, Herb & J. Smethurst, Christopher. (2010). Relationships between Flow, Self-Concept, Psychological Skills, and Performance. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology. 10.1080/104132001753149865.

- Scott‐Hamilton, J. , Schutte, N. S. and Brown, R. F. (2016), Effects of a Mindfulness Intervention on Sports‐Anxiety, Pessimism, and Flow in Competitive Cyclists. Appl Psychol Health Well‐Being, 8: 85-103. doi:10.1111/aphw.12063

- Linköping Universitet. (2017, March 1). Athletes’ symptom anxiety linked to risk of injury. ScienceDaily. Retrieved January 8, 2019 from sciencedaily.com/releases/2017/03/170301092702.htm

- Heckman, Christopher, “The Effect of Mindfulness and Meditation in Sports Performance” (2018). Kinesiology, Sport Studies, and Physical Education Synthesis Projects. 47. https://digitalcommons.brockport.edu/pes_synthesis/47

- Kaufman, K. A., Glass, C. R., & Arnkoff, D. B. (2009). Evaluation of Mindful Sport Performance Enhancement (MSPE): A new approach to promote flow in athletes. Journal of Clinical Sport Psychology, 3(4), 334-356.

- Haase, L., May, A. C., Falahpour, M., Isakovic, S., Simmons, A. N., Hickman, S. D., Liu, T. T., … Paulus, M. P. (2015). A pilot study investigating changes in neural processing after mindfulness training in elite athletes. Frontiers in behavioral neuroscience, 9, 229.

- Scott‐Hamilton, J. , Schutte, N. S. and Brown, R. F. (2016), Effects of a Mindfulness Intervention on Sports‐Anxiety, Pessimism, and Flow in Competitive Cyclists. Appl Psychol Health Well‐Being, 8: 85-103.